6/25/12: By Richard Weitz

Sino-Iraq relations will likely continue to strengthen in the near future.

China, which imports more than half its oil, needs Iraqi energy, while Iraq, which continues to suffer from sectarian violence and an unstable political environment, depends heavily on China’s willingness to invest in the country despite these lingering problems.

Yet, China’s policy towards Iraq is often mischaracterized as being determined exclusively by oil.

Unlike Iran and Saudi Arabia, Iraq has never been a major oil exporter to China.

Indeed, Beijing’s lukewarm opposition to the 2003 Anglo-American invasion partly resulted from China’s willingness to sacrifice Iraqi oil opportunities for other benefits, such as the U.S. government’s declaration that the “East Turkestan Independence Movement (ETIM)” is a terrorist organization and American assurances that the United States would not attack North Korea’s nuclear facilities.

Of course, China is not going to abstain from seeking opportunities to access Iraq’s oil or participate in other commercial ventures in the country.

Iraq’s relationship with China has expanded significantly since 2003. China has won stakes in 3 out of the 11 oil contracts offered by the Iraqi government in addition to renegotiating a Saddam-era deal worth around $3 billion. Chinese firms have been willing to reestablish relations with Iraq shortly after the U.S. invasion, and have since been willing to tolerate high levels of risk in order to gain access to some of Iraq’s most lucrative oil contracts. These deals have collectively made China the biggest investor in Iraq’s oil and gas industry, which has the world’s second largest proven oil reserves.

Iraqis are naturally eager to sign deals with China’s oil companies given their robust PRC government backing, their abundant investment funds, and their extensive experience working in challenging security environments.

Companies from many other countries have been reluctant to invest in the country due to continued political and economic turmoil, which has greatly hampered Iraq’s economic recovery. Chinese investors have proved willing to overlook these difficulties.

In 2009, the governments of China and Iraq approved a joint venture between CNPC, BP and the Iraqi government to revive the Rumaila field in southern Iraq. Much larger than al-Ahdab, Rumaila currently produces 1.06 million barrels a day; within seven years, CNPC plans to almost triple that production. Altogether, China has won four of the dozen contracts that the Iraqi central government has awarded since 2003. China also promotes security and stability in the region, a key component for investing in their oil and bidding on oil contracts.

The Iraqi government has also encouraged PRC companies to enter other economic sectors.

Iraq’s underdevelopment and lack of investment goes beyond oil, to encompass infrastructure of all kinds across the nation. Chinese firms are filling this gap. In addition to the oil sector, they have been investing in construction, government services and even tourism in Iraq.

The Chinese have made inroads into the cement industry, a significant and profitable business sector in Iraq given the numerous infrastructure projects. China has also built a power plant in southern Iraq and entered into negotiations with Iraq to construct residential facilities for laborers, to maintain compliance with Iraq’s restrictive investment laws.

Due to having complementary economies, the two countries saw a smooth development of trade relations until the 1990s, when China had to suspend economic relations with Iraq due to the Persian Gulf War. After the establishment of the new Iraqi Government in recent years, Chinese and Iraqi economic, military, and political relations have resumed in new developmental stage.

Beijing has recently taken steps to woo further deals in Iraq. In February 2010, the Chinese agreed to cancel 80% of Iraq’s $8.5 billion debt to China, a move that is considered likely to further help Chinese business interests in the country. This debt came on the heels of a two-year period (2009-2010) in which China and Iraq signed trade deals worth approximately $3.8 billion.

As currently structured, the China-Iraq relationship benefits both parties: Iraq receives much needed foreign investment and security assistance, while China gains access to coveted Iraqi oil reserves. Barring a significant deterioration in Iraq’s security situation, Iraq and China will likely continue to deepen both economic and diplomatic ties.

The United States and other countries arguably benefit from the presence of China and other states in Iraq, which dilutes Iran’s invariably large influence.

Some Iraqis and Chinese might also have this balancing idea in mind. In May 2010, the Chinese oil company CNOOC, in conjunction with a Turkish firm, began upstream work on the Maysan oil field, bordering Iran. The previous year, Iranian troops crossed the Iraqi border for a short time and seized the field. With Chinese companies developing Maysan and other Iraqi fields, and China’s growing economic stake in Iraq, Beijing will assert considerable pressure on Iran to avoid future troublemaking.

China will likewise encourage restraint in Baghdad with regard to both Iran and other Gulf states that export oil to China, such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

In addition, Iran’s influence with Beijing will decrease the more oil China can import from Iraq. The West needs Beijing’s support to pressure Iran to reign in its nuclear ambitions. China also shares the U.S. and Iraqi interest in avoiding renewed sectarian or other conflict in Iraq, whereas Tehran wants a weak and divided Iraq unable to resist Iranian influence.

This is not to say that the Sino-Iraqi relationship is cleared for smooth sailing.

Numerous domestic Iraqi issues over the distribution of oil revenues are hampering efforts to begin work on other fields. With concerns over how revenues from Kurdish fields will be spread, large-scale investment in those fields until a comprehensive oil law is passed is problematic.

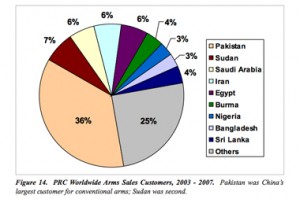

The PRC could also reemerge as a major arms seller to Iraq.

During the Iran-Iraq War from 1980 to 1988 China supplied weapons and military technology to both sides involved in the conflict and garnered about $8 billion in arms sales. From 1982 to 1989, China sold almost $5 billion worth of arms to Iraq, which represents 31.4 percent of all China’s arms sales during that period and over twice the value of Chinese arms sold to Iran in those years.

After the Iran-Iraq war Chinese arms to Iraq fell dramatically and then China completely lost Iraq as an arms customer at the onset of the Gulf War. Iraq’s poor performance during the Gulf War in the face of high-tech U.S. weapons further showed apprehensions about the quality of Chinese weapons systems in Iraq and the rest of the region.

In 2004, the 14-year UN weapons embargo ended, which enabled Iraq to refurbish its arsenal and take responsibility for its own security. Iraq was technically open to the arms trade since May 2003, when the country came under the governance of the Coalition Provisional Authority. The PRC resumed its arms sales in 2007 to Iraq when Iraq purchased $100 million of small arms for the Iraqi police. The sale was announced as a necessary measure since U.S. arms sales to Iraq were slow in coming.

The deal reflected Iraqi desires to reduce their dependence on U.S. arms supplies as well as dissatisfaction with the U.S. policy of arming Sunnis, who might oppose the new Shiite-dominated Iraqi regime. U.S. officials expressed concern because the Iraqi government did not have a clear plan for making sure that weapons were distributed, that they were properly monitored, and that they were repeatedly checked.

The U.S. government can only impose restrictions if the weapons involved were supplied by the United States.

U.S. intelligence later concluded that some PRC-made-weapons, as well as rocket-propelled grenades and surface-to-air missiles containing Chinese-made components, were being used against coalition forces or civilian targets in Iraq, while other PRC-made weapons have been obtained by militants in Afghanistan. U.S. analysts believe that China sold many of these weapons to Iran and that they were then diverted to insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Post-Saddam Iraq will likely purchase additional Chinese arms given Iraq’s conventional military weakness.

Whether measured in terms of tanks, artillery, or airpower, the Iraqi Security Forces are at a severe military disadvantage vis-à-vis neighboring powers. Chinese-made weapons, while qualitatively inferior to U.S.-made alternatives, will appear an attractive remedy given the delays inherent in the U.S. arms export system.

Furthermore, the Iraqi government would like to buy more Chinese weapons and receive some PRC military training as a hedge against relying excessively on the United States as Iraq’s main arms supplier. The United States might decide to cut off military assistance to Iraq for diplomatic, human rights, or other reasons. China has already proven a convenient safety valve for regional actors looking to insulate themselves against American interference in their internal affairs. Finally, the sale and prospects of future arms deals provide incentives for Beijing to support the Iraqi government.

Baghdad’s civilian leadership is also likely to look favorably on arms deals as a way to reinforce Iraq’s vital economic ties with the PRC. With civil-military relations in the country deteriorating, Baghdad needs Chinese investment to drive reconstruction for fear of military dissatisfaction deteriorating into armed action against the government.

If the Iraqi government can increase investment through closer political-military ties with Beijing, while simultaneously ameliorating its conventional weakness, Chinese arms will be perceived as a strategic bargain.

From Beijing’s perspective, arms sales are a convenient method for China to expand its economic ties with Iraq while augmenting its political influence both in Baghdad and the wider region.

Moreover, future arms sales to Iraq are unlikely to result in diplomatic balancing issues for China as none of Iraq’s neighbors perceive Baghdad as a looming conventional threat.

And profits from new arms sales will help fund the ongoing modernization of China’s defense industry.

Iraq boasts the Middle East’s second-largest oil reserves.

This presents a major opportunity for both lucrative investments and increased energy security. Furthermore, China’s augmenting its regional influence through arms sales and other measures can reduce U.S. leverage in the Middle East as well as regarding direct Sino-American issues.