2014-11-16 By Robbin Laird and Ed Timperlake

In mid-October 2014, we had a chance to discuss with Dr. Amatzia Baram, a leading Israeli expert on Iraq about how the ISIL crisis was much broader than simply being an Iraq crisis.

With several years of dynamic change in the region, and the failure to create a stable Iraq during the period after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, ISIL is like throwing a match into a gas can.

And the tensions in the divisions within the Middle East itself come into play and are augmented and aggravated by both responses to ISIL and the impact of success or failure in containing the impact of the ISIL movement.

Question: What’s your sense of how we should place the ISIS crisis in a broader regional context?

Baram: I see essentially two main very negative developments.

One is that Iraq will never be Iraq again, and I cannot see Syria becoming Syria again.

If you have this terrible instability, it’s a very, very hard on the other Middle East states.

They see this huge problem, and this is a spoiler of any hope for any stability.

I would still think the American administration has the right approach to see what they can do to try and put Humpty Dumpty back, when it comes to Iraq.

So my main concern would be how to bring stability back to this area by keeping Iraq as Iraq, and Syria as Syria, and saying that, which may be the case we should know within a few months.

The idea is to try and help a new architecture emerge that will enhance stability rather chaos.

That’s number one issue.

Number two, not less importantly, is that ISIS cannot be allowed more success.

They already had great success, but they have to at least be stopped.

I can see already all over the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Africa, the intellectual pull from ISIS as a radicalization virus spreading around much of the Islamic world.

In other words, if they are more successful, even though it may not create a total chaos where they are already, just the fact that they are so successful means that others will follow their example in the broader region.

Question: In other words, the impact of the ISIL brand has a demonstration effect in the Middle East and in Africa?

Baram: It is clearly the demonstration effect, which in turn impacts on the perceptions of GCC states as well.

The GCC states are of a kind of split personality with regard to ISIS.

If the ISIS were to conquer Baghdad, the GCC states can see a significant defeat for Iran and the Shias in Iraq.

With these two rivals being clobbered on the head, the GCC states come out ahead.

How bad can it be that Iran gets more than a bloody nose?

Yet an Isis seizure of Baghdad could well provide a significant demonstration effect in accelerating the kind of Islamic radicalism, which can destabilize the GCC states as well.

Clearly clobbering the Shias on the head is a good thing; yet by so doing it uncovers the hidden energies that can be mobilized by revolutionary Islam.

Question: America failed to put together a government in Iraq that was perceived to be anything other than one dominated by Shias.

The Maliki government was really nothing other than a Shia government leveraging the Iraqi assets to their benefit.

What then can be done in the face of the mobilization of Sunnis and Baathists currently being done by ISIL leadership?

Baram: In the current situation, one way out is to re-enter the reshaping of Iraqi politics, which can only be done by allowing the regions significant autonomy, and to broker their ability to provide for their own defense.

Then a confederation or a federated Iraq in effect could emerge.

If successful, this reshaped “unified Iraq” will serve as a stabilizing buffer in the region.

Given that the West will not deploy ground troops, certainly not in the numbers to allow for the kind of “brokering from above” which such capability could permit, the only force available currently to play a role and to shape a Western alliance with those with whom we might be able to work, are the Kurds.

The Turks have no intention of sending ground troops, for the current Turkish Administration is an ally of ISIL.

The Turks are brokering ISIL oil and selling it into the global market among other ways in which they are working with ISIL.

When it comes to the Iraqi forces, the military is not very effective.

They still have 14 divisions but only about four can more or less fight.

But they are certainly not willing to take big risks for Mosul.

Still, one reason why I do not think that Baghdad will fall to ISIL is that the Shia will fight for Baghdad, both in terms of the regular military and the militias.

Yet there is a serious problem of ISIL getting close enough for artillery barrages into Baghdad and for supporting terrorism in the city and putting pressure on the city in those ways.

The Kurds will fight and engage to push ISIL out of the Kurdish areas.

The Kurds will be very happy to help you on the ground if they are well armed, well directed, well tutored provided with air support from the U.S., or Europe, whatever.

So the Kurds can then take back the Kurdish areas if you support them.

With American support they have already pushed ISIL out of the Mosul Dam, north of the city.

But what to do about support for the Syrian Kurds?

Here Turkey comes into play; the support of the current Turkish Administration of ISIL is making the US Administration absolutely furious but not furious enough to provide weapons and other supplies to the Syrian Kurds.

And as far as the Turkish reluctance to allow the use of their airbase, it may come to choosing sides between ISIL and NATO.

This crisis is that serious.

The US could begin to build a new airbase in north-eastern Jordan (or expand the existing one there) to prepare to remove its reliance on the Turkish base, a position which might well prove necessary in the evolving politics in the region.

The Kurds have a clear agenda, but so do the Sunnis.

They do not want to be dominated by a Baghdad Shia government.

A way to turn them against ISIL is to provide for their ability to defend themselves against other forces within Iraq and outside of it.

Which means that first and foremost, they want a defense force that will protect them against anybody and everybody: of course, ISIL, but also the Iraqi National Army.

If you approach the Sunnis, all the Sunnis, with the idea of a “new” Iraq, there is a chance that you really can move them to your side.

But you see, right now they are in a bind because if they join you, and you don’t give them any guarantees for the future, why not just leverage the ISIL destabilization?

And if the Iraq Army occupies Mosul it will be viewed precisely as that by the Sunnis with the Shia seen to be occupying Mosul.

And the U.S. and allied role as an honest broker would simply not be possible.

Question: We have discussed Iran in passing with regard to the GCC states, but obviously Iran has a big stake in the crisis as well.

Baram: They do.

And one of the ironies of the current situation is that American policy against ISIL actually helps Iran.

Baghdad is now mostly an Iranian issue, more so than an American one.

You have to be aware of what America is doing.

America is getting Iran out of trouble by helping the government of Baghdad to push the ISIS back.

You are serving Iranian interests, not just yours.

So I’m not against it, as long as you understand what you are doing.

Iran will allow you to save it from ISIS, and in return they want you to allow them to continue to develop nuclear weapons.

Question: The ISIL crisis and its ongoing consequences will affect the great powers outside of the region as well; how do you see the stance of the major players?

Baram: With regard to Russia, they have little concern about Iran having nuclear weapons.

The Russians see this from the perspective of their conviction that they can unilaterally counter an Iranian nuclear threat effectively.

But what they have not calculated well is what others are going to do.

After Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and very likely also Turkey will acquire nukes.

A multi-player nuclear crisis is extremely difficult to control.

Even a nuclear war between Iran and Israel alone is dangerous for neighboring Russia, and one should bear in mind that unlike the Cuban missile crisis, there is no direct communication between Teheran and Jerusalem to provide key elements for negotiation as a crisis unfolds.

What does deterrence mean to Tehran as opposed to an old nuclear power like the United States or Russia?

How would a crisis management emerge that could manage these two very different poles?

And if Iran were to have access to nuclear weapons, notably with the onslaught of ISIL,or another similar anti-Shi`i movement, the use of nuclear weapons cannot be ruled out, and all this in close proximity to Russia.

Question: To put it mildly, this is a very volatile period of history, in which the calculations of key states in the region, all of whom have money, weapons, and power, could lead to a ratcheting up with the conflict here reasonably rapidly.

Is that a fair assessment of the challenge?

Baram: It is and this is why I focused on trying to keep Iraq Iraq and Syria Syria.

Even though far from perfect, this is a far better approach than simply allowing the crisis to spin out of control with unpredictable interactive consequences.

Prof. Dr. Amatzia Baram is a professor of Middle East History and Director of the Center for Iraq Studies at the University of Haifa.

Professor Baram was born in Kibbutz Kfar Menachem in southern Israel and raised and educated there.

He served as an officer and commanded tank units in the Armoured Corps during his regular military service from 1956 to 1960 and while in the reserves.

He was ‘on loan’ to the Iraqi desk at Military Intelligence as an analyst when soon after the Iraq-Iran War began in 1980.

After release from regular military service he worked on the kibbutz farm, before graduating in biology and teaching sciences at the kibbutz high school.

He decided on a career change following the Six Day War in 1967 and started his education as an historian of the modern Middle East and Islam in 1971

His latest book Saddam Husayn and Islam, 1968-2003: Ba’thi Iraq from Secularism to Faith came out in November 2014 by the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Johns Hopkins University Press.

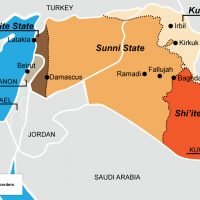

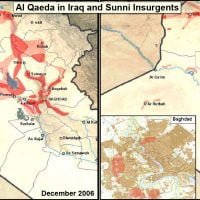

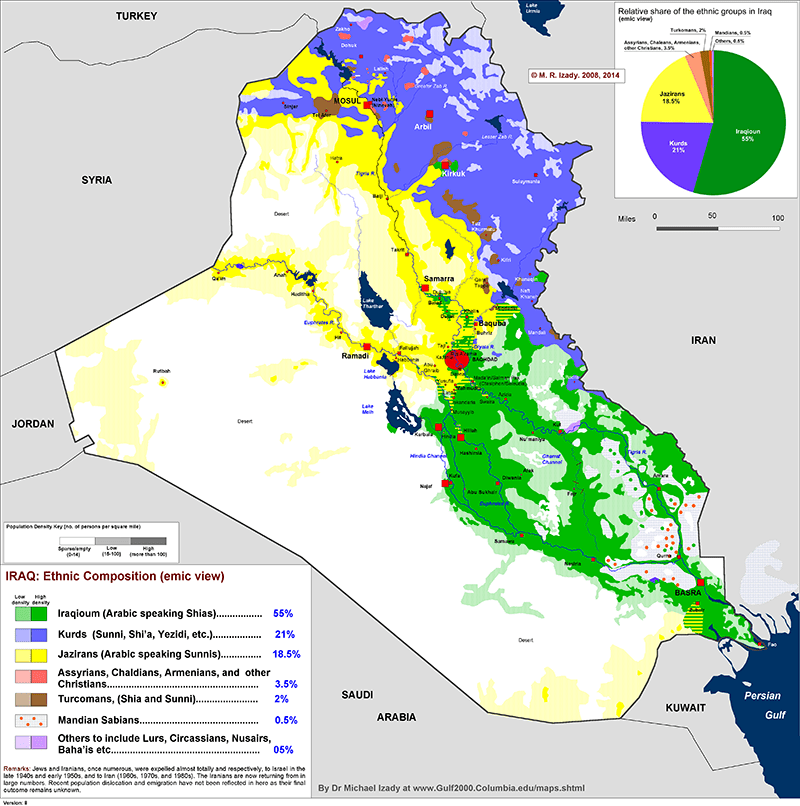

The maps have been taken from the article “27 Maps that explain the crisis in Iraq,” and the article can be found here:

http://www.vox.com/a/maps-explain-crisis-iraq

The first map shows Iraq’s three-way demographic divide didn’t cause the current crisis, but it’s a huge part of it.

You can see there are three main groups. The most important are Iraq’s Shia Arabs (Shiiism is a major branch of Islam), who are the country’s majority and live mostly in the south.

In the north and west are Sunni Arabs. Baghdad is mixed Sunni and Shia.

And in the far north are ethnic Kurds, who are religiously Sunni, but their ethnicity divides them from Arab Sunnis.

Iraq’s government is dominated by the Shia majority and has underserved Sunni Arabs; the extremist group that has taken over much of the country, ISIS, is Sunni Arab. Meanwhile, the Kurds, who suffered horrifically under Saddam Hussein, have exploited the recent crisis to grant themselves greater autonomy.

The second map shows the Kurds — who are long-oppressed minorities in Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Iran — have been fighting for their own country for more than a century.

They’ve come closest in Iraq, where, since the 2003 war, the international community has pushed to give them an unprecedented degree of autonomy.

Since the recent crisis began, they’ve taken even more de facto autonomy for themselves, and recently seized control of the oil-rich area around Kirkuk, which is part Arab and part Kurd.

The big problem for Kurds is that all of Iraq’s neighbors want to prevent an independent Iraqi Kurdish state, because they fear their own Kurdish populations will then fight to break off and join them.

The third map shows the rise and fall of the Sunni insurgency, 2006-2008.

ISIS was formerly known as al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI).

At its peak level of influence in 2006, AQI controlled significant chunks of Sunni Iraq, and even set up a quasi-government along harsh Islamic lines in some of the land it controlled.

However, the Sunni population turned on AQI — partly out of anger with AQI’s brutal rule and partly out of political interest.

This Anbar Awakening, named after the province in which it began, resulted in former Sunni insurgents partnering with the American and Iraqi militaries to uproot AQI.

AQI was roundly defeated, and lost effective control over almost all of its previous domain.

The fall of AQI illustrates just how much ISIS depends on support from Sunni Iraqis.

If it angers the population, they can provide critical intelligence and cooperation that would allow the Iraqi military to crush them.

The fourth map shows the Sunni protest movement of 2013.

Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki did a lot to assist in ISIS’s rise.

Since becoming Prime Minister in 2006, he has centralized a great deal of power in his office, and run the Iraqi government along Shia sectarian lines.

Naturally, this infuriated Sunnis, who organized a series of protests around the country in 2012.

These continued into 2013, and the Maliki government began to see them as a serious problem.

Unable or unwilling to resolve the protests politically, the Maliki government turned to force. His security forces killed 56 people at protest in the northern town Hawija alone in April 2013.

The forcible breakup of the protest movement convinced some Sunnis that their only solution was military, helping militant groups like ISIS and the more secular Jaysh Rijal al-Tariqa al-Naqshbandia (JRTN) recruit from and curry favor with the Sunni minority.

The fifth map shows a hypothetical re-drawing of Iraq and Syria.

This is an old idea that gets new attention every few years, when violence between Sunnis and Shias reignites: should the arbitrary borders imposed by European powers be replaced with new borders along the region’s ever-fractious religious divide? The idea is unworkable in reality and would probably just create new problems.

But, in a sense, this is already what the region looks like.

The Iraqi government controls the country’s Shia-majority east, but Sunni Islamist extremists have seized much of western Iraq and eastern Syria.

The Shia-dominated Syrian government, meanwhile, mostly only controls the country’s Shia- and Christian-heavy west. The Kurds, meanwhile, are legally autonomous in Iraq and functionally so in Syria.

This map, then, is not so much just idle speculation anymore; it’s something that Iraqis and Syrians are creating themselves.

One of the major questions facing Iraq, perhaps even bigger than the question of whether it can put down ISIS, is whether the government can overcome these sectarian divisions and make Sunnis, Shias, and Kurds feel that they are part of the same Iraqi state.

Until Iraqis believe in that project of a diverse, inclusive nation, and until the Iraqi government is able and willing to see it through, conflict is likely to continue.

Editor’s Note: For earlier articles on the evolving situation with regard to ISIL see the following:

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/in-iraq-back-to-the-tribes/

http://breakingdefense.com/2014/10/president-obamas-historic-middle-east-opportunity/

http://www.familysecuritymatters.org/publications/detail/confronting-schrecklichkeit-in-iraq

http://www.familysecuritymatters.org/publications/detail/revisiting-iraq-the-kurds-provide-an-option

http://breakingdefense.com/2014/09/its-not-airpower-vs-boots-on-ground-any-more/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/iraq-2014-crafting-strategic-maneuver-space/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/seizing-the-moment-in-iraq-shaping-an-effective-way-ahead/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/iraq-2014-is-not-iraq-2003-the-allied-dimension/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/iraq-2014-not-repeating-coin/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/revisiting-iraq-the-kurds-provide-an-option/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/the-iraq-dynamic-working-with-kurds-to-save-iraqi-christians/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/the-iraq-crisis-the-kurdish-opening/

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/isis-and-information-war-shaping-the-battlespace/