The Challenge of Crafting Integrated Missile Defense in NATO and Other Allied Regions

By Ambassador (Ret.) Jon D. Glassman, Director for Government Policy, Northrop Grumman Electronic Systems

Ambassador Glassman provides a two-part assessment of the challenge of building effective, integrated missile defense systems in NATO and in other regional allied settings. This part lays out the problem; the second part identifies some paths to resolution of the problem. [1]

10/28/2010 – As NATO considers assumption of homeland territorial ballistic missile defense (BMD) as an alliance mission at the Lisbon Summit in November, and as Israel, the countries around the Persian Gulf, and Japan proceed with their own BMD acquisition, missile defense now moves beyond the exclusive focus on engineering and development to the realm of operations.

The transition to operations draws in a new set of decision-makers — national political leaders and military commanders — each with priorities going beyond simple physical functionality of systems.

The priorities of these decision-makers in each theater need to coalesce in regional or parallel bilateral understandings on the objectives of missile defense and the means of its execution. If the political leaders and military operators do not create collective or synergistic approaches, the inadequate weight of the theater missile defense effort may render it futile — leaving only pre-emptive offensive action as an option.

Regional missile defense architecture—in the hoped-for world of political and military concord—will have to embody more than wire-diagram connectivity of systems.

Additionally, a consensus must emerge that will stimulate self-sustaining growth and transformation of missile defense in the face of evolving threats through mutually reinforcing investment and cost savings produced by coordinated and parallel operations.

For the last 45 years, debate has centered on the physical practicality of missile defense: could a bullet hit a bullet? Mercifully, that debate has ended and, in the face of looming threats from Iran and North Korea and uncertainties in Eurasia, real investments are now being made by the United States and other nations to provide a rudimentary and, eventually, more robust homeland and regional defense against missile attack.

As missile defense goes operational, architectural and engineering studies are underway within regions to knit together U.S. sensors and shooters—and, in the future, those of partners—in networks allowing command-and-control. These networks and directive capabilities will be stressed in some regional contexts because of short timelines between launch and impact and the weight of incoming numbers.

The need to create an effective response to voluminous challenges within rigid time constraints makes investment, operational, and policy planning/coordination imperative; yet this vital need is only beginning to be recognized in regional missile defense discussions.

Why is it important to get these issues right?

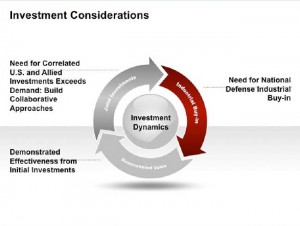

Investment Considerations

- The US, as a technological and thought leader, has identified impending threats and moved to forward-deploy naval and land missile defense assets. This presence, particularly in Europe, cannot be sustained politically within the U.S. absent reciprocal investment by regional partners.

- States undergoing severe fiscal stress—much of Europe and Japan—need formulas allowing investment to benefit national defense industries at a yield no less than the budgetary bite. Otherwise investment will not be feasible.

- In places where partner investment has occurred (Japan and the Persian Gulf), newly-acquired missile defense assets must be made to work effectively—to be cued and enabled in time to produce reliable defense. Without this, these initial investments will be seen by regional partners ultimately as wasteful and will not be repeated. The expense of missile defense guarantees that total numbers of sensors and shooters will always lag the offensive threat. This provides strong incentive to promote partner missile defense sensor and interceptor acquisition via imports and, in some cases, domestic production.

- The growing likelihood of raids (multi-missile salvos) and combined ballistic and cruise missile assault makes advisable pre-planned coordination and resource management of total U.S. and partner defensive assets, both sensors and shooters. This, in turn, requires electronic and cyber protection and decentralized control, at least as a default.

- The high value of defended assets (heavily-populated and critical to economic well-being), and the likely quantitative asymmetry between threat and defense, make timely and coordinated offensive action by defenders a potential necessity to mitigate the volume and duration of attacks. Offense-defense fusion with partner attack assets is, therefore, highly desirable.

- The provision of strategic and tactical warning, and subsequent battle damage assessment, requires the consolidation of U.S. and partner air and space intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities and correlation of their data; the process of engagement must be defined as beginning well “left of launch.”

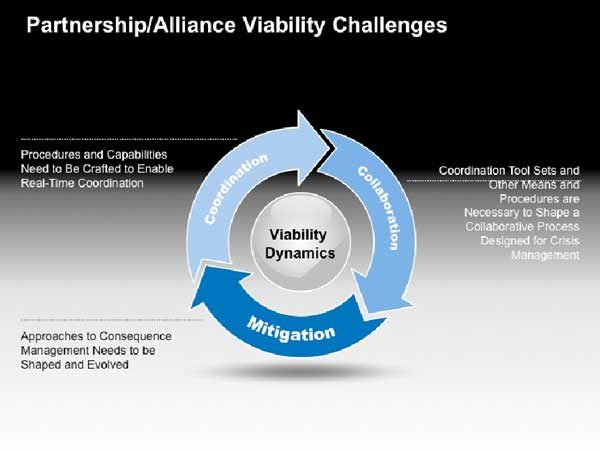

Partnership/Alliance Viability Considerations

- The deployment of U.S. and partner interceptor assets in regions—beyond the need for military technical effectiveness—creates a requirement for U.S., partner, and alliance agreed processes to accomplish pre-conflict consultation, undertake joint/collective diplomatic and political-military action, grant weapons release authority, establish rules of engagement, and accommodate national and regional sovereignty concerns.

- Policies and capabilities need to be in place to deal with demands on interceptors to cross/not cross third-party airspace, to de-conflict with civilian and military air traffic, to avoid third-party confusion between offensive and defensive action, and to deal with on-ground damages and liability claims arising from interception.

- National and regional systems should be created to enable technically the agreed policy processes and outcomes: minimally providing collective situation awareness, facilitation of communication and collaboration, and exercise of positive control over defensive and offensive assets.

- Regional capabilities and procedures need to be established to mitigate the human, economic, and military consequences of missile attack and engagements, to include chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear explosive (including electromagnetic pulse [EMP]), and satellite effects.

- Beyond the military requirement to reconstitute and sustain defensive and offensive assets and enablers, the macro-economic consequences of missile penetration must be dealt with, both in the directly effected region and those burdened by secondary and tertiary problems occasioned by transportation, energy, and trade disruption.

Toward Integral Missile Defense (Credit: SLD)

As outlined above, the requirements for regional missile defense go far beyond the simple deployment and support of sensors and shooters and their connection into networks. The integration of sensors and shooters into networks is a necessary building block, but is insufficient in itself to deliver the comprehensive construct of broad-spectrum threat defeat and mitigation, optimal use of resources, political/economic coordination and planning, and continuing investment required to ensure long-term defense.

Integrated air and missile defense is but a part of the needed integral defense of regions embracing:

- Defeat of the full range of threats, both ballistic and air-breathing: rockets, artillery, and mortars (RAMs) to theater ballistic missiles, powered glide bombs and UAVs to long-range air-to-ground missiles and cruise missiles

- Effective cooperation across time: from threat gestation (pre-launch indications and warning) through detection/tracking/engagement, offensive action, and consequence management/reconstitution

- Achievement of optimal defensive effect through efficient allocation of defensive resources and offensive-defensive fusion

- Enabling of coordinated investment strategy and political-military policy determination and execution

The next part of this piece will provide recommendations on how integral missile defense can be implemented in NATO and in other missile-threatened regions.

———

[1] The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Northrop Grumman Corporation nor the US Government.