By Richard Weitz

Russia’s current Prime Minister and future President, Vladimir Putin, makes evident that the Russian government will not soon follow the Obama Administration towards nuclear disarmament.

For example, on February 24, 2012, he told the media that Russia will not make any further unilateral or even bilateral cuts in its nuclear forces unless other countries possessing nuclear weapons join in the strategic arms reductions process.

“We cannot disarm endlessly while some nuclear powers are arming themselves,” Putin insisted. “No way.”

In addition to requiring that future nuclear arms control occur on a multilateral process, though without specifying whether these must be formal negotiations involving all countries having nuclear weapons or a smaller group of participants in which reductions can occur through unilateral action, Putin also insists that Russia cannot reduce its nuclear forces further until it improve the strength of its conventional forces, citing in particular Russia’s lagging capabilities in the area of precision-guided munitions (PGMs).

Putin joins others in arguing that the accuracy, yields, and rapid speed of modern PGMs “make them comparable in their effects to weapons of mass destruction.” As a result, “We will only abandon nuclear weapons when we have such systems, and not a day earlier,” he said. “No one should have any illusions about that.”

Pending these two developments, Putin affirmed that Russia would seek to maintain strategic parity with the United States — having equivalent offensive nuclear power notwithstanding U.S. strategic defenses — in order to deter Washington from engaging in unilateral actions that threaten Russian security. Moscow, like Beijing, does not want to make the world safe for U.S. conventional military superiority.

In his recent Moscow News article on Russia’s foreign policy goals and outlook, Putin rails against what he calls the U.S. quest for “absolute security.” In his words, the problem is that “absolute invulnerability for one country would in theory require absolute vulnerability for all others.” Instead, Putin again insists on the right of all states to equal security, as well as Russia’s right to maintain the capacity to attack the United States with nuclear weapons if necessary.

In Moscow’s view, the problem of equal security also applies to the conventional force imbalance in Europe, where Russian officials complain about how NATO’s preeminent role in European security harms their national security since they have little impact on alliance decisions.

The United States recently joined Russia in ending implementation of the original Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty. Russian officials have also given up on the idea of ratifying the Adapted CFE Treaty approved at the 1998 Istanbul Summit, since NATO insists that Russia withdraw its military forces from Georgia as part of its Istanbul Commitments.

Given these complications, Russians are uninterested in various U.S. proposals for a “grand bargain” that would seek to address both the CFE and the non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe issue.

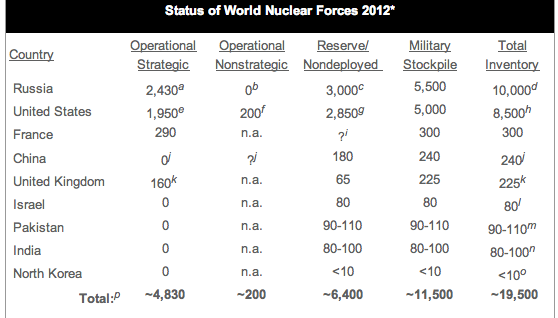

These latter “tactical” nuclear weapons (TNW) are of special concern for Washington since Russia possesses many more of these weapons than does NATO and the United States.

Russia also has many more different types of these weapons. The United States, having recently retired the nuclear-armed variant of its submarine-launched Tomahawk Land-Attack Cruise Missile (TLAM/N), now has only a single gravity bomb delivered by land-based aircraft. In contrast, Russia’s non-strategic arsenal of nuclear delivery vehicles including anti-ship cruise missiles, air and missile defense missiles, anti-submarine systems, land attack and anti-ship ballistic missiles, nuclear-armed torpedoes, as well as gravity bombs for use by Russia’s land- and sea-based aircraft.

Despite these obstacles to further nuclear arms control, Russia has stopped threatening to withdraw from the New START agreement — the treaty came into force last year– unless the United States further constrained its missile defense program. This threat was never very credible because Russian analysts presumably assessed how U.S. BMD might adversely affect Russia’s nuclear deterrent before agreeing on the treaty’s provisions, including its duration until 2020. It is more likely that Russia will resist beginning new formal strategic arms reduction talks until shortly before New START expires.

In fact, the New START Treaty’s implementation is going well, with no major complaints from either side.

In his February 27 foreign policy article, Putin writes that, “The treaty has come into effect and is working fairly well. It is a major foreign policy achievement.” During the first year New START was in force, both sides exercised their full quota of 18 on-site inspections. They also exchanged almost 2,000 notifications of changes in the location or status (i.e., in-and-out of maintenance) of their nuclear weapons, which for the first time includes unique identifiers for each system. The three sessions of the Bilateral Consultative Commission that have occurred (two in 2011 and one in early 2012) also addressed such knotty issues as telemetry (the assured access to the other party of some data sent by missiles in test launches).

Moving forward, the Obama administration wants to make reductions in three categories of nuclear weapons, two of which have never been covered in previous strategic reduction talks involving Russia, the United States, or anyone else.

The administration wants to discuss going below the current New START limits of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads and 800 (deployed or non-deployed) strategic delivery vehicles for each side. But U.S. officials also would like to cover “non-deployed” strategic nuclear weapons (warheads that are kept in reserve or storage but are still functional and can be rapidly deployed) as well as “non-strategic” (commonly referred to as “tactical”) nuclear weapons.

All previous negotiations have applied limits exclusively to strategic offensive nuclear forces. Previous negotiations did not cover these non-deployed systems or warheads because verifying any limits on the number or status of nuclear warheads not mated to their strategic delivery vehicles would require more intrusive measures than simply counting their long-range delivery systems and applying various simplifying counting rules to estimate the number of warheads they likely carry.

The emerging U.S. preference is to use a common ceiling for all these types of nuclear weapons.

This total operational inventory would cover strategic and nonstrategic warheads, whether deployed or non-deployed. In early 2010, the United States disclosed that its total inventory consisted of 5,113 “active” nuclear warheads (i.e., those not removed from service and awaiting retirement).

The Russian total is probably close to that, but the Russian sub-totals are distributed differently, with fewer warheads in storage but many more on shorter-range systems. This could require some complex trade-offs or sub-ceilings, but it could also prove suitable for a simplifying agreement in which each side is free to deploy its treaty-limited warheads on any deployed system or non-deployed status as long as they remain below the overall ceiling.

In the past, Russian strategists expressed great alarm about a superior U.S. “upload” potential. To hedge against technical failure or adverse geopolitical developments, the United States keeps many more non-deployed strategic nuclear warheads than Russia, which remanufactures its warheads more rapidly due to having less faith in their likely operational service life.

In addition, the United States has been meeting its nuclear arms reduction agreement requirements by removing warheads from its delivery vehicles while keeping them in service. These could be easily returned to the delivery vehicles in a crisis. Meanwhile, Russia has been eliminating its aging Soviet-era missiles along with their warheads, while slowly seeking to rebuild its forces.

As a result, the United States presently could, more easily than Russia, rapidly increase its arsenal of deployed nuclear warheads by augmenting its existing delivery vehicles with their full potential load of warheads.

To decrease this “upload” potential, Russia has regularly sought to require further reductions in U.S. nuclear delivery systems. The United States is offering to address this disparity by agreeing to eliminate more of its non-deployed warheads as part of a common warhead ceiling on both sides, in which Russia would eliminate more of its non-strategic warheads, reducing that disparity as well.

Russia’s planned buildup in its strategic nuclear delivery systems equipped with multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) should also help decrease the problem by boosting Russia’s own “upload” potential.