By James Durso

The U.S. and its main Persian Gulf partners, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have had a falling out in recent days.

The causes are both immediate and long-term and each party feels the blame lies with those ingrates on the other side.

Recently, the kingdom and the UAE refused to pump more oil to make up for the loss of Russian oil in the market in the wake of the war in Ukraine, and help to reduce the price at the pump in the U.S.

Both countries signaled their support for OPEC+, which counts Russia as a member, and the UAE oil minister explained, “We need their [U.S.] understanding that what we’re doing is to the benefit of the consumers, to the benefit of the United States and to the benefit of the consumers worldwide.”

In addition, the UAE abstained from a UN Security Council (UNSC) vote condemning the Russian attack on Ukraine, reportedly in frustration over U.S. the response to attacks by Houthi rebels on the emirate, though it later voted for a UN General Assembly motion condemning the attack.

Saudi Arabia’s de facto leader Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) avoided U.S. president Joe Biden by being a no-show at the G20 meeting in March, and not being on the line during Biden’s recent phone call with Saudi King Salman.

But MBS did manage to pick up the receiver to talk to Russian president Vladimir Putin, and the kingdom invited China’s leader Xi Jinping to visit the kingdom this Spring. (UAE leader Mohammed bin Zayed (MBZ) also ghosted Biden when the White House wanted to discuss the oil crisis.) MBS shrugged off Biden’s negative opinion of him with, “Simply, I do not care.”

During his visit to Riyadh, Xi will be sure to advocate that the kingdom should accept Chinese yuan for oil sales in a move to minimize China’s exposure to the U.S. financial sector and increase its financial leverage.

This has been talked about for a long time, but the time may finally be right as thinking about the end of the dollar’s dominance no longer seems far-fetched.

If the Saudis agree and lock in a long-term forward contract, Xi would return to Beijing in triumph before the 20th Party Congress, where he expects to be named to a third term as China’s paramount leader, his position made unassailable with the yuan enshrined as a petro currency, and the position of the US Dollar weakened.

Now, who wouldn’t want that IOU in his pocket?

Both sides should consider practical steps to get the relationship on a better footing, but what should Washington consider if it moves to do so?

First, how you treat your friends is more important than how you treat your enemies.

MBS and MBZ likely absorbed the appropriate lessons when the U.S. quickly dropped longtime U.S. client Hosni Mubarak after two weeks of protests. Washington then supported a UNSC resolution it then used as justification to attack Libya, causing the capture and death of the leader Muammar al-Qaddafi, the destruction of the country, and an unprecedented refugee crisis in Africa and Europe. In 2016, when some guy named Biden worked in the White House, then-president Barack Obama supported efforts to oust Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

More recently, the U.S. limited arms sales to Saudi Arabia to “defensive” weapons only, in an attempt to curb the kingdom’s fight against the Iranian-sponsored Houthi militia. Then the Biden administration reversed the Trump administration designation of the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, which may have encouraged the movement to increase attacks on the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

The U.S. sale of the F-35 fighter to the UAE has been delayed over U.S. concerns about the surveillance ability of China’s 5G wireless network located near UAE airfields, and the U.S. desire for operational restrictions, which the emirate understands to mean it can use the aircraft to support U.S. foreign policy, but not its independent moves.

Recently, the UAE, after a U.S. demand, terminated a Chinese-funded $1 billion project in the Khalifa Port Free Trade Zone the U.S. said had military applications. U.S. President Joe Biden spoke about the project to Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed who said he heard Biden “loud and clear,” though the emirate later declared, “our position remains the same, that the facilities were not military facilities.”

This must seem like Groundhog Day for the UAE.

In 2006, Dubai-owned DP World was forced to back out of an approved purchase of port management contracts at six major U.S. seaports after the U.S. Congress opposed the deal. Sixteen years later the UAE is learning it can’t even conclude a seaport project at home without a U.S. intervention.

As a result of the U.S. arm twisting, the UAE may have to make an offsetting accommodation to China, its top trade partner, that the U.S. will like even less, a prime example of “it seemed like a good idea at the time.”

The UAE and Saudi Arabia have no doubt noted that Israel, America’s top ally in the region, also came in for its share of abuse by Washington, so at least there’s misery in company.

In January, as the Russian troop buildup on Ukraine’s border continued, the U.S. withdrew its support for the EastMed natural gas pipeline from Israel to Greece. In 2020, Washington pushed Israel to stop Chinese investments in large infrastructure projects, most recently the new Haifa Port, the largest container port in Israel.

And the U.S. administration appears heedless of Iran’s declaration that Israel is “doomed to disappear.” Or maybe it just doesn’t care.

Most distressing for the U.S. friends in the Gulf, is Washington’s mad dash to revive the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which was originally negotiated without any role for Iran’s neighbors, who will be most immediately threated by an unconstrained Tehran. The JCPOA negotiating team did include far-away Germany, likely as a sop to Europe, though, ironically, Germany was a source of much of the nuclear technology on Iran’s clandestine shopping list.

And recently, the crown princes (and the world) witnessed America’s livestreamed retreat in Afghanistan, as it blithely abandoned two decades of effort, $2 trillion dollars, and several thousand of its Afghan helpers and U.S. citizens to the mercies of the Taliban.

That was likely a clarifying moment for the princes who now knew that all that shona ba shona (“shoulder to shoulder”) stuff in Kabul was just talk, and they would be wise to diversify their portfolios.

Next, insult diplomacy doesn’t work.

Joe Biden famously called Saudi Arabia a “pariah” with “very little social [sic] redeeming value” for the killing of activist Jamal Khashoggi, and which should make for some awkward moments if Biden ever has to visit the kingdom.

Now, MBS no doubt commissioned Khashoggi’s killing, but he’s famously thin-skinned and is on the cusp of a multi-decade run as the leader of Saudi Arabia.

And the U.S. has no ability to influence succession planning in the kingdom, which was plain when Washington’s favorite, then-crown prince Muhammad bin Nayef, was ousted.

(Pro tip: a political figure who’s the public favorite of foreign security services doesn’t stand a chance.)

Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump, got much better results as he wasn’t averse to transactional diplomacy and he understood that do deal with a crown prince, he had to send his own crown prince, Jared Kushner, someone with walk-in privileges at the Oval Office.

He managed to get the UAE to sign on to the Abraham Accords, which probably required Saudi assent. Trump also appealed to the Saudis to reverse a planned oil export increase – which they did, even though it aided the U.S. oil and gas industry.

President Ronald Reagan likewise got the Saudis to act in America’s interest when he urged them to help defeat the Communists by depressing the price of oil, slashing the Soviet Union’s revenues and accelerating the collapse of the USSR. Both presidents understood that dealing with the royals required a personal touch or the opportunity to be the preferred partner in an epochal undertaking, i.e., destroying Godless Communism.

Today, MBS knows he can outlast the outbursts from the older man whose health challenges are increasingly obvious, though Biden’s deteriorating health poses some risk to the kingdom.

America’s manic pursuit of a new nuclear deal with Iran will leave Saudi Arabia and the UAE exposed to Iran’s export of revolution in pursuit of regional hegemony.

Bolstered by access to embargoed overseas cash, and the de-listing of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, Iran’s moves will cause these friends to hedge by increasing trade and cooperation with China, Russia, and India, and not cooperating with U.S. policies when they have no stake in the outcome, i.e., Russia vs Ukraine.

Biden’s policy is seen as a continuation of Obama’s intent that Saudi Arabia needs to “share” the region with Iran, an Iran that has declared, “there will be no trace of Al Saud in Saudi Arabia by 2030.”

In late 2021, news reports indicated Saudi Arabia is building, with China’s help, solid-fuel ballistic missiles. Though the effort pre-dates the Biden administration, the state of the kingdom’s relations with the U.S. may encourage Riyadh to consider development of non-conventional warheads.

Not surprisingly, Saudi observers see the U.S. pursuit of Iran as the end of the relationship.

Mohammed al-Yahya, the former al-Arabiya editor-in-chief, declared, “When Barack Obama negotiated the nuclear deal with Iran, we Saudis understood him to be seeking the breakup of a 70-year marriage…Why should America’s regional allies help Washington contain Russia in Europe when Washington is strengthening Russia and Iran in the Middle East?”

And while the Saudis fret, Dubai is welcoming Russians (and their flight cash) and may have soon have to grapple with the “problems” of an overheated luxury property market and a shortage of Russian-speaking salesmen at luxury car dealerships.

Diversifying the portfolio is more than ignoring U.S. requests to pump more oil, pricing oil in yuan, and welcoming Russians.

It’s also about exercising autonomy by, say, hosting Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad in the UAE, much to Washington’s ire, which will also give Moscow a foreign policy win in its support for Damascus, a diplomatic partner of Moscow since 1944 (Moscow was the first foreign capital to establish diplomatic relations with Riyadh – in 1926 – though the relationship included a 54-year break.) The Emirati view: “Our new approach emphasizes diplomacy, de-escalation and engagement … and we put our own interests first.”

But can we still be friends?

As it looks to the multi-polar future, Washington should consider that its securitization of the relationships in the Gulf has created the expectation in the Gulf countries, who have relied on the U.S. for 45% of their arms imports in recent years, that all that cash was buying a security guarantee.

The U.S., which was too busy counting the money, may not have understood the expectation it created so, when it turned its back on Afghanistan, made concession after concession to woo Tehran, and demanded the Gulf states fall in line with its anti-Russia policy, the loss of confidence was serious and Russia, China, and India may be more reliable partners for the long haul.

James Durso (@james_durso) is a regular commentator on foreign policy and national security matters. Mr. Durso served in the U.S. Navy for 20 years and has worked in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq.

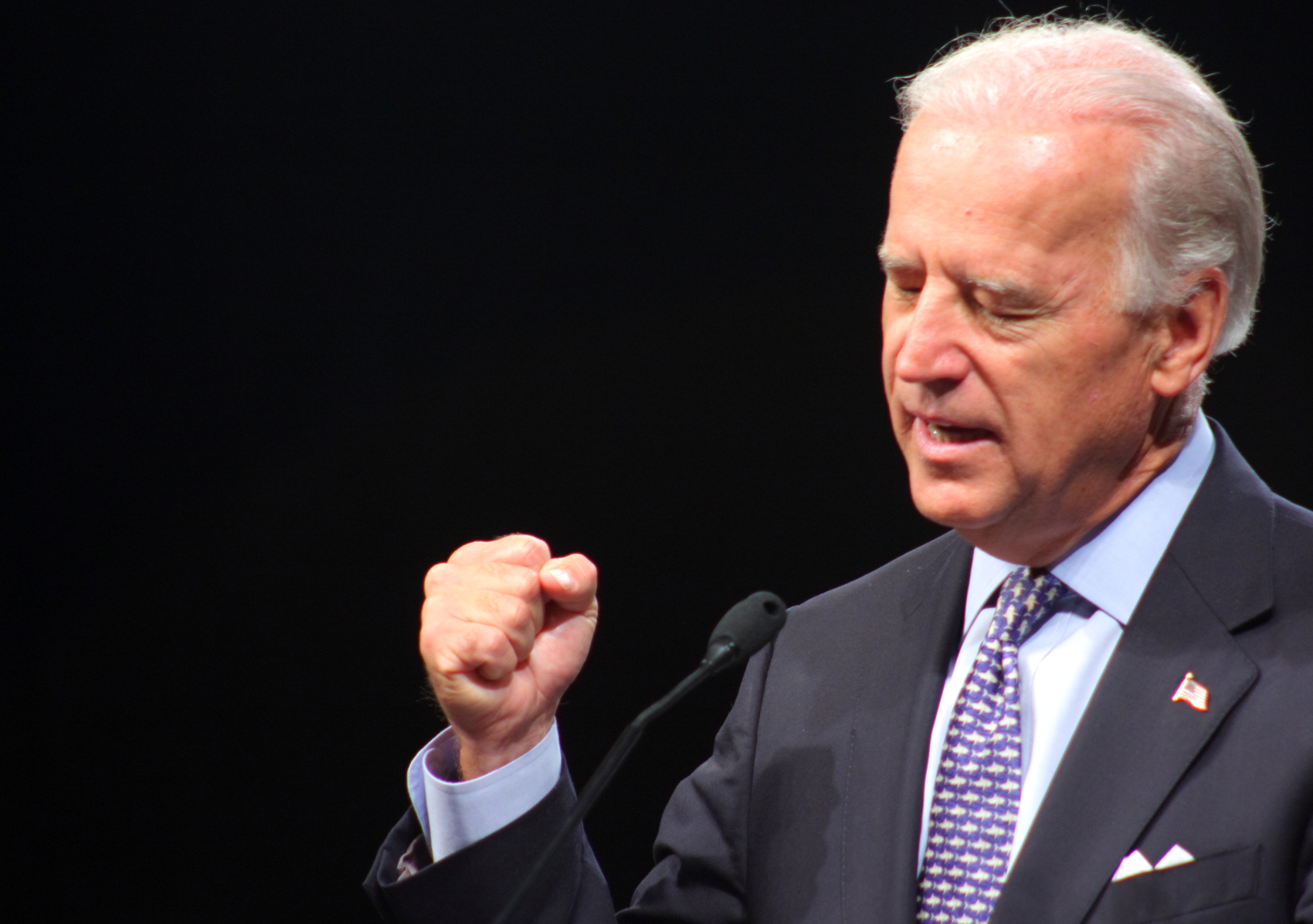

Featured Photo: Photo 6304947 © Benjamin Vess | Dreamstime.com