2012-09-17 By Richard Weitz

The Japanese government continues to allocate approximately one percent of the country’s GDP to the military, a fairly low level compared to most countries.

But the enormous size of Japan’s economy means that even this formula generates one of the largest defense budgets in the world. Japanese spending supports a sophisticated and modern military force even while coping with structural inefficiencies such as the national policy of favoring domestic arms suppliers despite their high costs due to their limited production runs.

To respond to the new threats and opportunities discussed earlier, the Japanese government has been seeking to substitute quality for quantity throughout the SDF.

These forces consist of a ground, maritime and air service.

The Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF) is the largest of the three services, with a total of some 150,000 personnel. The Maritime Self-Defense Force and the Air Self-Defense Force each number approximately 50,000. The JSDF also has some 40,000 reserve personnel.

Since the 1990s, moreover, Japan has been taking steps to bolster its homeland defenses.

In December 2001, the Japanese Coast Guard sunk a presumed North Korean spy ship outside Japan’s territorial waters, signaling a harder line to such intrusions. The government has since begun equipping the Coast Guard with faster and longer-range patrol boats. Maritime clashes with China have been reinforcing this trend.

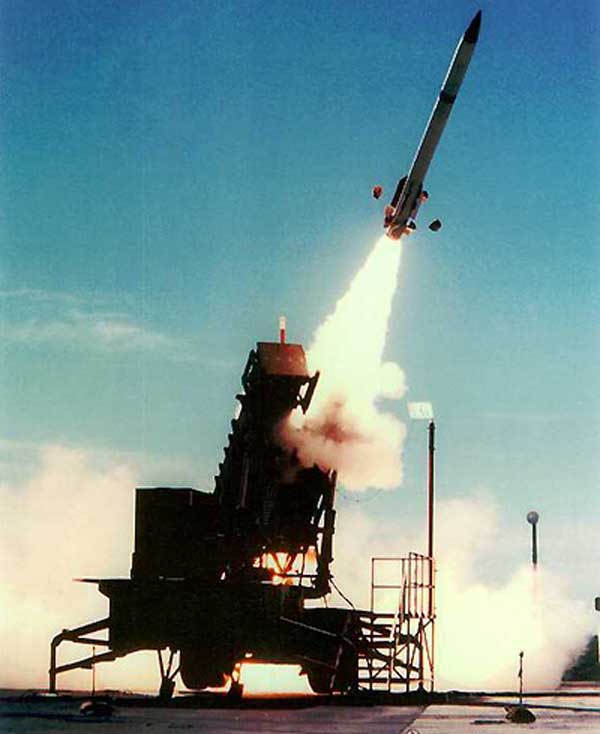

The government continues to modernize Japan’s armed forces, developing, purchasing, and acquiring sophisticated fighter planes, warships, and other advanced capabilities.

A recent priority has been to develop capabilities for supporting military operations beyond Japan’s territory.

Japan is currently acquiring long-range air refueling tankers, 13,500 Hyuga-class helicopter-carrying destroyers (Japan’s largest warships since World War II), and other weapons systems that will enhance its ability to project power beyond the immediate home islands.

In 2007, for the first time since World War II, Japan conducted live bombing exercises (in conjunction with the United States) over Guam. For the exercise, Japan deployed its F-2s, which were able to fly the 1,700 miles from northern Japan to Guam without refueling. Japan also practiced dropping 500-pound live bombs on Farallon de Medinilla with the U.S. Air Force in the summer of 2007.

Since 2003, Japan has launched its own space reconnaissance satellites.

Although their presumed purpose is to monitor military developments in North Korea such as preparations for missile launches, another function might be to gather information on China. Japan’s advanced civilian space program could presumably provide the foundation for developing a national capability to destroy satellites.

Nevertheless, the immediate factor behind Japanese interest in developing power projection capabilities is not to conduct military strikes against North Korea or the Chinese mainland.

Rather, they aim to increase Japan’s ability to interoperate with U.S. forces in multinational missions as well as to enable Japan to protect the vital sea-lanes that sustain the national economy, which remains heavily dependent on foreign commerce.

These sea-lanes have helped Japan become one of the most impressive national economics in world history, especially given the country’s limited indigenous resources. Emerging from the devastation of World War II, Japan enjoyed unprecedented economic development for most of the second half of the twentieth century, due in large part to its minimal expenditures on Japan’s national defense, which primarily became an American responsibility.

Guided by the “Yoshida Doctrine,” a post-World War II political strategy named after Japan’s first post-war prime minister, Japan generally avoided costly foreign military activities in favor of economic advancement and strategic cooperation with the United States.

The Japanese government renounced nuclear armament, fixed military spending at no more than one percent of its gross domestic product (GDP), and enacted a series of broad economic reforms encouraging technological investments, international trade, and the rapid expansion of industry.

These reforms, coupled with minimal defense spending, spurred astonishing growth—more than 10 percent annually from 1955 to 1970—and helped Japan become the world’s second-largest economy by 1972.

By the time the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991, Japan had established itself as a dominant technological power and world’s largest creditor country. One observer remarked at the time: “The Cold War is over and Japan has won.”

But then Japan’s economy fell into two decades of stagnation, when scandals involving government officials, bankers, and leaders of industry—compounded by the Asian Economic Crisis of 1998—placed Japan in an economic depression that it continues to this day.

Overinvestment, including the purchase by Japanese companies of such U.S. commercial establishments as Rockefeller Center and Pebble Beach Golf Course, coupled with the asset price bubble of the late 1980s prompted the government to lower interest rates and encourage banks to lend, resulting in massive asset price inflation and the tripling of stock and urban real-estate prices. Once the bubble burst in the early 1990s, asset prices and banks collapsed and unemployment reached postwar highs.

Unable to adapt its highly-bureaucratized, producer-oriented economy to the liberalized and increasingly competitive post-Cold War marketplace, Japan entered a “lost decade” of economic and political stagnation worsened by higher oil prices, weaker investor confidence, and lower equity prices. Economic growth—a robust 4 percent annually during the 1980s—has slowed to around 1-2 percent per year since 1990.

According to the World Bank, Japan’s recent growth rates have been the following:

- 2007: +2.2%

- 2008: -1.0%

- 2009: -5.5%

- 2010: +4.4% and

- 2011: -0.7%

The Japanese lost hundreds of billions of dollars from the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami, with additional losses due to disruptions in the national supply chain. The country’s trade balance fell into deficit.

Efforts to revive the economy have largely proven unsuccessful, due in part to the government’s inability to secure major structural reforms and the economic slowdowns that have also affected Japan’s main trading partners such as the United States and the European Union.

Public debt remains a problem at more than 200 percent of GDP. Japan’s more enduring structural problems include difficulties in competing with lower-cost producers and in shifting to higher-value added business.

This diversification of Japan’s trade portfolio has insulated Japan from the weaknesses of the U.S. and European economies, but it has not helped Japan’s large service sectors enjoy renewed prosperity because they depend primarily on domestic customers, whose numbers are declining due to population decline..

Demographics present a long-term problem for the country’s national security community. Japan’s birthrate has fallen well below the 2.5 rate required to keep the population constant at approximately 125 million people. The population stopped growing a few years ago. In addition, the largely homogenous country has traditionally been unenthusiastic about immigration. As a result, the population is aging, with a growing proportion of non-working retirees. In 2040, some 40 percent of Japan’s population is projected to be at least 65 years old.

These trends will reinforce structural problems with the Japanese economy, whose prosperity generates the revenue the armed forces require to acquire their expensive domestically manufactured equipment. For example, government spending on social security will likely rise in coming years at the expense of possible military spending.

In addition, demographics complicate efforts to recruit and retain sufficient personnel for the SDF, which must pay competitive wages given the country’s lack of conscription.

Even so, it is important not to exaggerate the extent of Japan’s economic problems. Although far from the double-digit expansion of the 1960s and early 1970s, growth continues, driven by business investment and strong exports, fueled in particular by rising demand from Asia for the country’s manufactured products.

The country has the third-largest national economy, worth almost six trillion dollars, which places Japan behind only the United States and China.

It is arguably the second most technologically influential economy in the world. Japanese leaders are aiming to establish Japan’s dominance of emerging strategic fields including recycling, transportation, designing and publishing, next-generation energy solutions (hybrid cars, solar power, low carbon fuels, etc.), and advanced technologies such as aerospace and nanotechnology.